People born in Turkey are most likely to move to an area with a high number of their Turkish compatriots, according to the 2011 Australian census. Areas such as Meadow Heights, in Victoria, with around 20% of its populace born in Turkey are popular destinations for Turkish migrants. Despite only comprising 0.15% of Australia’s population, the median local prevalence of Turkish-born residents is 9%.

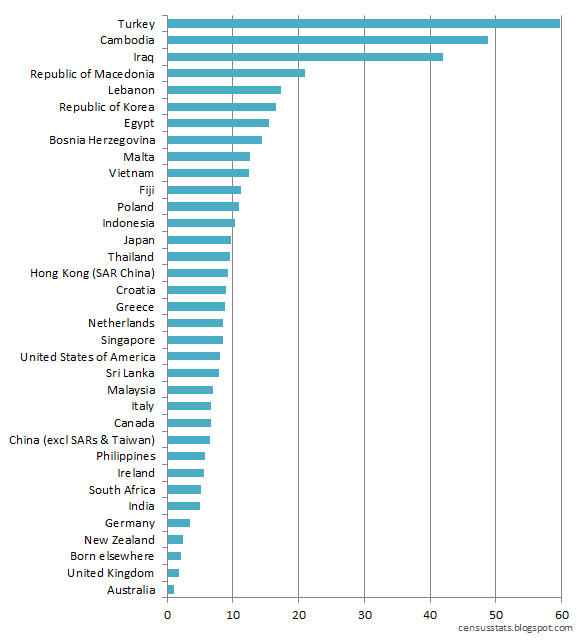

The chart below ranks migrants in Australia by their tendency to cluster with their national compatriots. This measure is based on a ratio that compares their proportion of the wider population with the median prevalence of compatriots within their local Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) boundaries.

Second place belongs to Cambodian migrants, who tend to cluster together disproportionately to their prevalence in the wider population. Despite making up only 0.13% of Australian residents, their median local prevalence is 6.4%. Springvale, a suburb in Melbourne, which comprises 23% Cambodian, and 15% Vietnamese residents, paints a fairly typical picture of a south-east Asian enclave. Likewise, more than 50% of the population of Cabramatta, in New South Wales, was born in Cambodia or Vietnam, according to the 2011 census.

Iraqi migrants are the third most likely to cluster with their fellow Iraqis. As mentioned in a previous post, this can be explained by the disproportionate degree of Iraqis that migrate via Australia’s Humanitarian Programme. Having fled their own war-ravaged nation, moving to areas with some of the familiar comforts of home makes sense.

Arguably the most impressive spread of migrants are those born in China. Despite vast cultural differences, the Chinese are the tenth least clustered of 35 nations measured, and less so than many European nations, including Italy, Greece and Poland. Chinese people make up 1.5% of the Australian population, and their median local prevalence is 9.79%. This spread of Chinese demonstrates that the common perception that Chinese people cluster around Chinatown areas is a fallacy.

This pattern indicates that migrant sources typically begin in localised clusters, then spread out more evenly across the nation as their numbers increase. It can be expected that these initial clusters portray many of the cultural traits of their homeland, and help migrants to feel secure in a foreign land. As their scale increases within Australia, this leads to cross-cultural flows of influence between Australian and the expanding migrant culture. This, in turn, evolves into a hybrid, containing elements of both cultures and further supporting an even spread of migrants through a continual feedback loop.

Mature examples of migrant source nations are the United Kingdom and New Zealand. The results of this cultural feedback loop are visible as the three nations share many cultural traits. Australia, as a result, continues to be attractive to migrants from these nations as a consequence. It can therefore be expected that in the future the Chinese and Indian feedback loops will gather pace, feeding into the very definition of ‘Australian culture’.

The chart below ranks migrants in Australia by their tendency to cluster with their national compatriots. This measure is based on a ratio that compares their proportion of the wider population with the median prevalence of compatriots within their local Statistical Area Level 1 (SA1) boundaries.

Second place belongs to Cambodian migrants, who tend to cluster together disproportionately to their prevalence in the wider population. Despite making up only 0.13% of Australian residents, their median local prevalence is 6.4%. Springvale, a suburb in Melbourne, which comprises 23% Cambodian, and 15% Vietnamese residents, paints a fairly typical picture of a south-east Asian enclave. Likewise, more than 50% of the population of Cabramatta, in New South Wales, was born in Cambodia or Vietnam, according to the 2011 census.

Iraqi migrants are the third most likely to cluster with their fellow Iraqis. As mentioned in a previous post, this can be explained by the disproportionate degree of Iraqis that migrate via Australia’s Humanitarian Programme. Having fled their own war-ravaged nation, moving to areas with some of the familiar comforts of home makes sense.

Well Spread

At the other end of the scale, the Brits, New Zealanders, Germans, Indians and South Africans are relatively spread out across Australia. As a Western nation, it is hardly surprising that other Western nationals, such as those from the United Kingdom find it easy to integrate with the wider population. The spread of Indians can also be explained by the significant Western influence in the subcontinent, not least of which is a familiarity with the English language.Arguably the most impressive spread of migrants are those born in China. Despite vast cultural differences, the Chinese are the tenth least clustered of 35 nations measured, and less so than many European nations, including Italy, Greece and Poland. Chinese people make up 1.5% of the Australian population, and their median local prevalence is 9.79%. This spread of Chinese demonstrates that the common perception that Chinese people cluster around Chinatown areas is a fallacy.

Migrant Scale vs Clustering

There is a general trend that the smaller the amount of migrants from a given nation, the higher the degree of clustering. This trend is stronger among the nationalities that comprise less than 1% of Australian residents.This pattern indicates that migrant sources typically begin in localised clusters, then spread out more evenly across the nation as their numbers increase. It can be expected that these initial clusters portray many of the cultural traits of their homeland, and help migrants to feel secure in a foreign land. As their scale increases within Australia, this leads to cross-cultural flows of influence between Australian and the expanding migrant culture. This, in turn, evolves into a hybrid, containing elements of both cultures and further supporting an even spread of migrants through a continual feedback loop.

Mature examples of migrant source nations are the United Kingdom and New Zealand. The results of this cultural feedback loop are visible as the three nations share many cultural traits. Australia, as a result, continues to be attractive to migrants from these nations as a consequence. It can therefore be expected that in the future the Chinese and Indian feedback loops will gather pace, feeding into the very definition of ‘Australian culture’.

0 comments:

Post a Comment